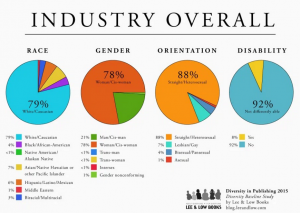

Part of the results of a 2015 survey of US publishers (courtesy of Lee and Low Books)

We are living through an unprecedented era of culture wars, where debate about diversity and cultural representations of the “other”, especially in terms of gender, race, sexual orientation and disability, are set against the backdrop of the very real-life effects of inequality. Movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter demonstrate that we are a long way from resolving the battles for equality that dominated the civil rights movements of the late twentieth-century Western world.

It could be argued that the real world is now lagging behind the arts, or even completely at odds with it, especially given the reversals of liberal democracy most evident in the votes for Trump and Brexit. The dominance of literary prizes (and prize juries) by straight white males is (largely) a thing of the past. TV programmes such as the excellent adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale have struck a chord with audiences. While Hollywood has a distance to go on that front, stronger roles, in front of and behind the camera, for women, LGBTQ people and people of colour are finally becoming a reality – if not the norm.

But it would be naïve to think that equality of roles and representation are within reach, and opinions are divided as to where we go from here. Recent surveys in both the US and UK demonstrated how much publishing, for instance, remains a predominantly white middle-class industry in terms of staff. Author Lionel Shriver’s recent controversial comments about the proactive diversity policies of publisher Penguin Random House, were met with a swift rebuttal by PRH as well as condemnation from fellow writers such as Hanif Kureishi.

PRH’s policy in the UK is designed to bring its publishing acquisitions programme, and its new hires, in line with the make-up of the general UK population. But Shriver argues that such policies are not about diversity, but about creating quotas – something which, she feels, pushes quality into second place, only after certain boxes have been ticked.

Leaving aside Shriver’s provocative scenario that “an incoherent, tedious, meandering and insensible pile of mixed-paper recycling” would be published if it were written by “a gay transgender Caribbean who dropped out of school at seven and powers around town on a mobility scooter” – if it’s that bad, then no, it wouldn’t be published, no matter who wrote it – there are strong arguments on both sides. Let’s instead assume that two writers submit two objectively excellent manuscripts, equal in quality, to a publisher with a diversity policy. Might the writer who fulfils certain diversity criteria be offered a publishing contract at the expense of the equally talented writer who does not fulfil these criteria?

The problem with this argument is that it implies that there has to be a winner and loser in such circumstances, whereas publication decisions are, in general, not a matter of either/or. A savvy publisher will want to publish both. Of course, budgets are limited, even among large publishers, and only a certain number of new writers are likely to be acquired each year, so yes, quotas could, potentially, lead to some writers losing out overall, at least in the short term. My own feeling is that, ultimately, talent will out, and that the same factors that have always helped talented writers find their audience will continue to work in their favour over the long term: persistence, hard work, patience, opportunity and luck.

There is also an implication that we can easily compare two completely different works of art. Yes, literary prizes do this all the time, as does our continuing obsession with list-making and “top tens”. But judging a novel’s merit can never be entirely objective, and that subjective judgement happens first at the point of decision to acquire a novel or not.

Which brings me to the other side of the argument: it is the editor who makes the first subjective judgement of a novel’s worth, and decides to bring it forward to acquisition. But does the editor not bring their own subjective, culturally determined taste to bear on this decision, informed of course by their professional knowledge of the market? And if editors are predominantly, say, from a white, educated, middle-class background, will they be in the best position, subjectively, to judge the merits of a novel written by an author from a very different background?

So, with a more diverse, representative editorial team, might the gems that could otherwise be overlooked stand a better chance of shining? Might an editor from a minority background respond more to a manuscript written by a writer from the same background – and, crucially, relatable primarily to readers from a similar background? Might the championing of such “new” voices create new audiences among those frustrated by a dearth of books that speak to them of their own lives? And, if this happens, might these new voices create role models that future generations might follow? Might a budding young writer who previously saw no point in using their time creatively now feel that, yes, there are people out there who want to hear what I have to say?

PRH’s policy makes commercial sense – it is a business, after all, and its altruism does not exist in a vacuum. Creating a more diverse, representative list is likely to create new audiences, without losing its current audiences. In other words, it opens new markets and expands its customer base, allowing the company to publish more books. And, in the long run, this would mean that there would be space on its list for talented writers, no matter what their background.

But there is a distance to go. Sharmaine Lovegrove, publisher at Little, Brown’s inclusive imprint Dialogue Books, told The Guardian: “For decades, you have had white, middle-class people acquiring books by white, middle-class people. I’m a black, middle-class woman who lives in London with Jamaican heritage and I speak German, having lived and worked in Berlin. All of that, when I’m looking for stories, makes my prism much wider than that of some of my colleagues in the broader industry, yet my difference highlights an issue rather than being celebrated for its insights, and that is exhausting.”

Writing in The Guardian, Chitra Ramaswamy put it succinctly: “Equality and quality are not mutually exclusive” and greatness “can come from anywhere”.

In my next post, I’ll be picking up on the related issues of cultural appropriation, “sensitivity editing” and self-censorship.

In my MA class some years ago I asked the professor (thinking perhaps of Mozart or Tolstoy) if there was such a thing as a universally accepted work of art. The professor winked.